The Review and Herald reported that “all felt that the institution was and would be a complete success. On September 5, 1866, the institute was formally opened, with “two doctors, two bath attendants, one nurse (untrained), three or four helpers,” and “one patient.” 10 There was room available for 12 patients, and before the month ended all rooms were occupied and the staff had to scramble to provide more rooms and assistants. In a few days he and other leaders purchased a farm in Battle Creek pertaining to Judge Graves for $6,000, and on this site was developed the Western Health Reform Institute. Loughborough succeeded in raising $11,000 in all. Kellogg, $500,” before adding, “There it is, ‘sink or swim.’” 9 A few of us have decided to make an investment for the purpose presented to us in that testimony, ‘sink or swim.’ We thought we would like to have your name at the head of the list, as you have more money than any of us.” 8 According to Loughborough’s chronicle, Kellogg promptly took the paper and signed, “J. “Brother Kellogg,” he began, “you heard the testimony that Sister White read to us in the tent. Kellogg, one of the wealthier Adventists in Battle Creek, Michigan. After praying for a time, Loughborough and his committee said, “we will pledge to the enterprise, venturing out on what is said in the testimony, though it looks to us like a heavy load for us to hold up.” 7 Drawing up a subscription paper, Loughborough went to John P.

Since James White was ill, the responsibility for creating a health institution fell on John Loughborough, president of the Michigan Conference. The testimony finished, the people in the tent began asking themselves how a small Church could put such mammoth plans in motion.

BATTLE CREEK SANITARIUM HOW TO

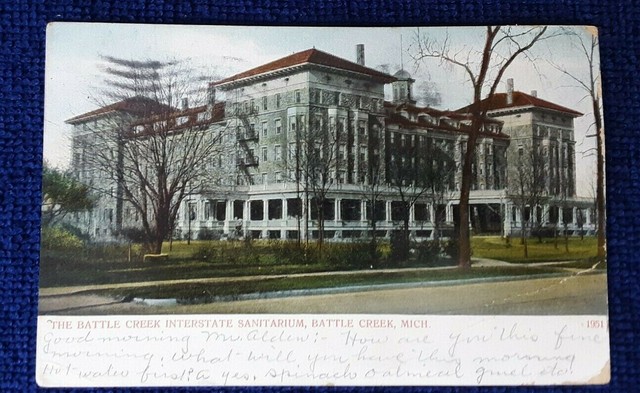

God desired that the Adventists “should provide a home for the afflicted and those who wish to learn how to take care of their bodies that they may prevent sickness.” White urged that Adventists “should have an institution of their own, under their own control, for the benefit of the diseased and suffering.” If rightly conducted, the institution would “be the means of bringing our views before many whom it would be impossible for us to reach by the common course of advocating the truth.” Even though White acknowledged that many in the Church needed treatment in such an institution, she argued that the main purpose of a health center was to convert patients to the Church. In the opening lines she rebuked the audience, stating that “our Sabbath keeping people have been negligent in acting upon the light which God has given in regard to the health reform.” 5 But there was still hope. 4 For the first time, she read the contents of the vision she had seen on Christmas Day, 1865, regarding health reform. On May 19, Ellen White addressed the General Conference delegates gathered in a 50-foot tent erected on the location where the Dime Tabernacle would later stand. 2 Smith wrote that “as in times of prosperity it is proper to enumerate our blessings, so now in this time of adversity and humiliation let us enumerate our calamities.” After listing the calamities, a season of prayer was appointed, from May 9 to 12, 1866, to “be set apart as special days of humiliation, fasting and prayer on the part of the church.” Smith hoped that the special days would see God “revive his cause, remove his rebuke from off his people, restore his servants, and lead on the message to its destined victory.” The upcoming session of the General Conference only served to add urgency to Smith’s prayer request. Many well-known ministers and leaders, including James White, John Andrews, Joseph Bates, John Byington, John Loughborough, and Daniel Bourdeau, were afflicted by one malady or another. Uriah Smith, editor of the Review and Herald, wrote that “instead of an increase of laborers, many of the more efficient ones then in the field, have been either entirely prostrated, or afflicted in some way calculated to dishearten or cripple them.” 1 The founders of the newly created Seventh-day Adventist Church were struggling to keep the scattered bands of believers together, and they were disappointed to see petty results from the effort of their labors. The war’s desolation was visible in all quarters, from politics to religion. Though the Civil War had officially ended by 1866, its devastating aftermath was just beginning. Western Health Reform Institute (1866-1876) The Battle Creek Sanitarium was a world-renowned Adventist health resort in Battle Creek, Michigan, United States.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)